Although many doctors today use robots to assist them in procedures such as hernia repairs and coronary bypasses, these robots are meant to aid surgeons, not replace them. This new research represents a step forward in developing robots that can perform more complex tasks, such as suturing, with greater autonomy. The insights gained from this development could also be applied to other areas of robotics.

“From a robotics perspective, this manipulation task is extremely challenging,” says Ken Goldberg, a researcher at UC Berkeley and the director of the lab that created the robot.

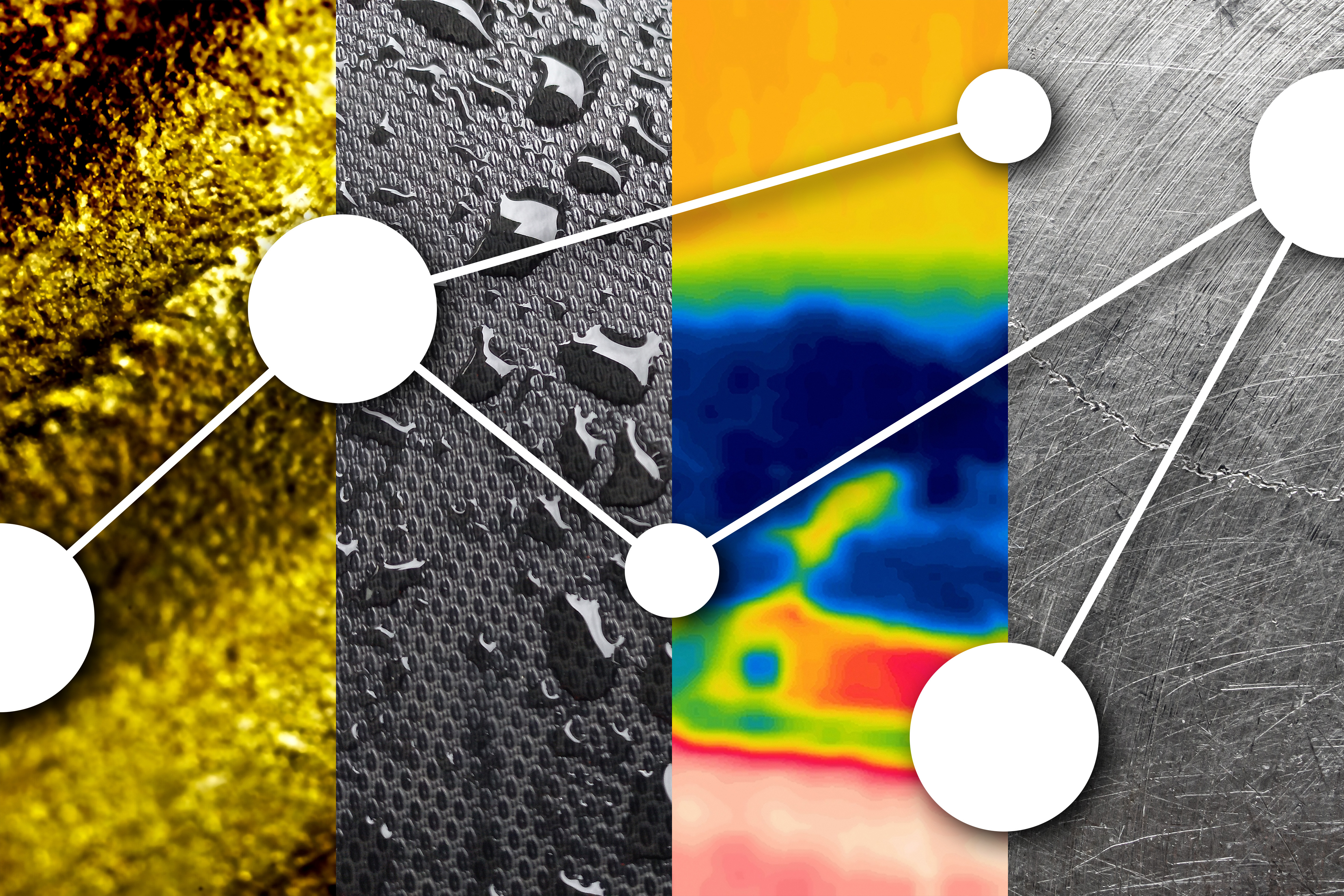

One challenge is that shiny or reflective objects, like needles, can interfere with a robot’s image sensors. Additionally, computers struggle to accurately model the behavior of “deformable” objects, such as skin and thread, when they are manipulated. Unlike passing a needle between human hands, transferring a needle between robotic arms requires a high level of dexterity.

The robot uses a pair of cameras to observe its surroundings. Trained on a neural network, it can identify the needle’s location and use a motion controller to plan the six motions needed to make a stitch.

While we are still far from seeing these robots independently perform suturing in operating rooms, automating part of the suturing process holds significant medical promise, according to Danyal Fer, a physician and researcher involved in the project.

“There is a lot of complexity in a surgery, and suturing is often the final task,” Fer explains. Surgeons may be fatigued while suturing, and improper closure of a wound can lead to extended healing times and other complications. Because suturing is a repetitive task, Goldberg and Fer believed it was a suitable candidate for automation.

“Can we demonstrate improved patient outcomes?” Goldberg asks. “While convenience for the doctor is important, the ultimate goal is to achieve better sutures, faster healing, and reduced scarring.”

COURTESY OF KEN GOLDBERG

However, the success of the robot comes with limitations. The machine was able to complete six full stitches before human intervention was required, but it averaged only about three stitches across trials. The test wounds were limited to two dimensions, unlike wounds in curved areas of the body like the elbow or knuckle. Furthermore, the robot has only been tested on “phantoms,” simulated skin used in medical training settings, and not on actual organ tissue or animal skin.